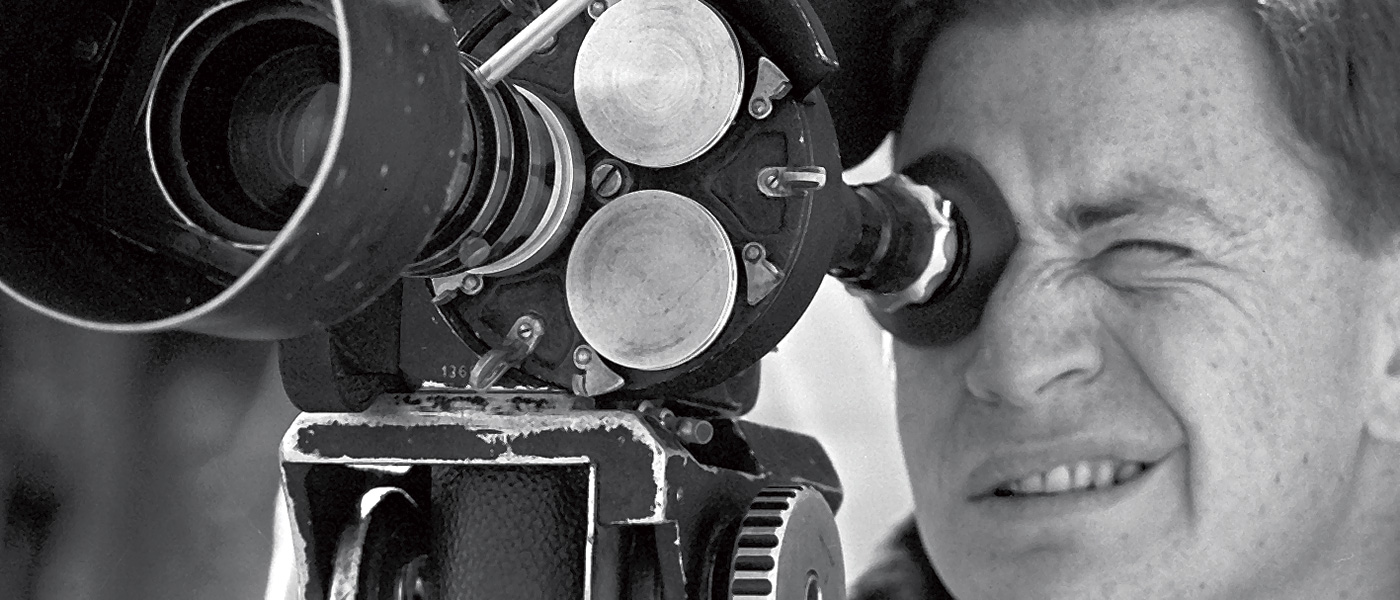

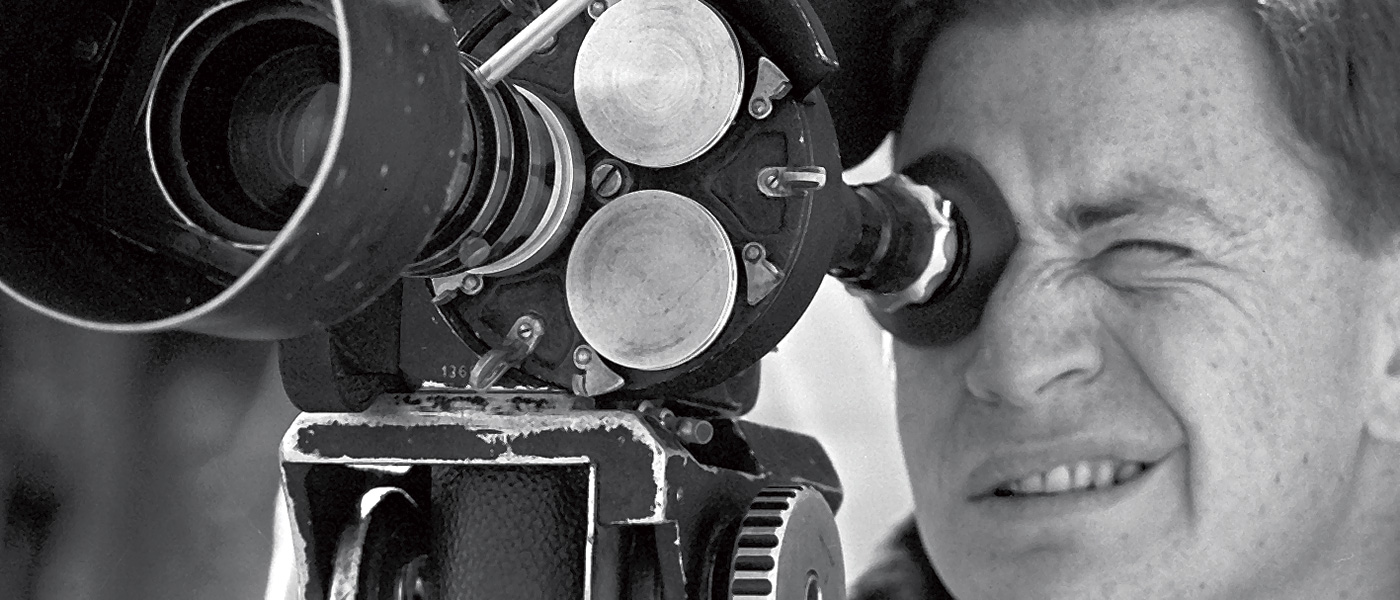

Istvan Szabo – critical note & biography

Critical note

Istvan Szabo belongs to that generation of people who were twenty years old when the events of 1956 took place in Hungary. To be precise, he was eighteen when the Soviet tanks entered Budapest and twenty-three when he shot Koncert, the short lm with which he later graduated from the University of Theatre and Film Arts in 1963. This is to say that, for an author like Szabo?, it is inevitable to nd the reasons for making lms in a direct confrontation with a sense of history experienced rst-hand, as something that goes beyond events because it belongs to experiences that have not yet been processed and metabolised. His view of reality stems from the need to place the individual in the complexity of his own personal time, confronting it with historical events. The theme of the individual’s responsibility in the face of the choices that history imposes on them is the frame of a mirror re ecting the image of a moral dimension of existence, which has to come to terms with the existential niteness of the individual, with their fragility, with the compromises that their character, emotions and the contingency of the moment impose on them.

Szabo?’s cinema is a journey of growth. It begins with a generational approach, with lms that dialogue with the present in the agrancy of youth approaching adulthood, and then gradually nds a metaphorical dimension to relate to the past. In the end, it leads to an elaboration of history through the responsibilities of the individual and the faults of the community. This is the evolution of a “humanistic” vision of reality (Comuzio), which enabled the director to nd a universal or, better said, international language, thanks to which he became, not by chance, the best known Hungarian lmmaker of his generation in world cinema, awarded in the major festivals and invited to work in large-scale co-productions boasting the presence of notable lm stars.

It all started, though, with his early experiences, when he was totally immersed in the spirit of his time, his eyes focused on the vibrant experience of the French Nouvelle Vague, which inspired him to create a trilogy narrating the approach of his generation to adulthood with an overtly Tru autian inspiration, not only in style but also in the use of a fetish actor, who for Szabo? was Andra?s Ba?lint: The Age of Daydreaming captures the emergence into adulthood of a group of young people who have just nished their studies, while Father describes the confrontation with reality of a boy grown up with the idealistic myth of his father (in which it is not di cult to glimpse references to Stalin) and Love Film reconstructs recent Hungarian history, dealing with the theme of the gap between reality and feelings. Szabo? was “one of the rst, during the start of the Ka?da?r administration, to deal with private stories, to play the card of recovering subjectivism with great expressive success” (Bolzoni), and in these lms there is an immediacy that certainly stems from the atmosphere of the Be?la Bala?sz Studio, which Szabo? and his fellow Academy students (Ja?nos Ro?zsa, Pa?l Ga?bor, Ferenc Kardos, among others) had refounded. These three lms were followed by the diptych composed of 25 Fireman’s Street and Budapest Tales, which brought a more metaphorical dimension to the director’s cinema, in which the lens seems to widen and the whole of Budapest becomes the symbolic scenario of a vision that is increasingly embodied in Hungarian social and historical reality. The subsequent Con dence, combining the intimate encounter between two lonely lovers with the historical dimension of the post-war period, acted as a hinge with the following triptych, which marked the beginning of the great international period, characterized by an explicit re ection on the relationship between power and society, or rather between ambition and the individual.

These are themes the director dealt with again later on with di erent formulations, but they are precisely formulated in the 1980s trilogy marked by the presence of Klaus Maria Brandauer: Mephisto, Colonel Redl and Hanussen. It is here that history becomes an evident element of moral confrontation for the individual who, faced with the responsibility of making choices, must disentangle among his own dreams, the reality into which he has been plunged in spite of himself and the nal judgement that awaits him implacably. Everything that followed was a re ned variation on these themes, through a series of lms that, in the language of major international productions he had by then acquired, explored a dilemma that, in the eyes of the director, appeared to be the true junction between the dreams and disillusions matured in the shadow of the post-was period, whether we are taking about the fall of the Soviet empire (Sweet Emma, Dear Bobe), artistic ambitions (Meeting Venus), sentimental vanity (Being Julia) or connivance with the horrors of history (Taking Side).

Massimo Causo

Biography

Born in Budapest on 19 February 1938, Istvan Szabo was one of the main protagonists of the season of renewal of Hungarian cinema inaugurated in the 1960s. Grown up in Tatabanya, a mining town in North-western Hungary, where he lived until almost the end of the war, Szabo? went to school in Budapest and, after graduating from high school, was admitted to the University of Theatre and Film Arts. There he attended the classes held by famous director Fe?lix Ma?ria?ssy and made his rst short lms: A Hetedik napon (1959), Plaka?tragaszto? (Bill Poster, 1960), Variaciok egy te?ma?ra (Variations on a Theme, 1961), Te (You, 1963) and Koncert (The Concert, 1963), his graduation lm. Together with his fellow students, in 1961 Szabo? refounded the Be?la Balasz Studio, set up in 1959 as a movie-goer club and then transformed by the students into a production studio thanks to the spirit of modernisation promoted by Ja?nos Kadar’s reforms.

It was in this context that Szabo debuted aged just 26 with Almodozasok kora (The Age of Daydreaming, 1964), the rst instalment of a trilogy that, along with the subsequent Apa (Father, 1966) and Szerelmes lm (Love Film, 1970), represents an ideal biography of his generation. All of these works stood out on the international festival scene, as did the following two lms: Tuzolto utca 25 (25 Fireman’s Street, 1973), winner of the Grand Prix at Locarno 1974, and Budapesti mese?k (Budapest Tales, 1976), in Competition at Cannes 1977. These two lms make up a diptych in which Budapest becomes the symbolic place of a vision that was being increasingly embodied in the social and historical reality of his country. The subsequent Bizalon (Con dence, 1979) followed the same direction, describing the atmosphere of distrust at the end of the Second World War by showing the forced cohabitation of a couple of strangers in a at. The lm earned Szabo? the Best Direction award at the Berlinale and an Oscar nomination, as evidence of the international prestige the director was acquiring.

After a short period in Germany, where he lmed Der gru?ne Vogel (1980), a love story set during the Cold War, Istva?n Szabo? started, in fact, a new phase in his career, characterised by a re ection on the relationship between history and the individual, based on themes related to the moral responsibility of man when dealing with power. Such is the framework of Mephisto (1981), a drama about an actor’s complicity with Nazism in the name of art, based on the novel by Klaus Mann: starring a compelling Klaus Maria Brandauer, the lm won Best Screenplay at Cannes and an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, which paved the way for a great international success. Along the same production and thematic line are also Colonel Redl (1984), in which the director chose Brandauer again to portray the parable of an ambitious young o cer of the Austro-Hungarian army, and Hanussen (1988), in which the Austrian actor embodied the true story of a German psychic who rose to great fame in Nazi Germany.

By then moving in an international context, Szabo? began the 1990s with Meeting Venus (1991), in which Glenn Close and Niels Arestrup are the protagonists of a satire about the relationship between ambition, art and feelings centred on an attempt to stage an innovative Tannha user in Paris. In the subsequent E?des Emma, dra?ga Bo?be (Sweet Emma, Dear Bobe, 1991) the director focused, instead, on the disorientation following the fall of the Soviet regime, by telling the story of two country girls who try to survive in the new reality. The subsequent two lms too show that the confrontation with history is the perspective privileged by Szabo?: in Sunshine (1999) Ralph Fiennes tells the story of three generations of a Jewish family, from the Austro-Hungarian Empire to the Second World War; Taking Side (2001) reconstructs the trial involving the famous orchestra conductor Wilhelm Furtwangler, accused of collusion with Nazism. The contrast between the lure of artistic success and personal life is central again in Being Julia (2004), in which Annette Bening brings to life the story of a waning leading lady from London in the 1930s. The following lms marked Istva?n Szabo?’s return to his homeland: Rokonok (Relatives, 2006) is a social satire about a young and honest attorney struggling with corruption, At Ajto (The Door, 2012) is a drama set in the 1960s about the ambiguous relationship between a young Hungarian writer and her strange housekeeper, while the recent Zarojelente?s (Final Report, 2020) stars again Brandauer as a renowned cardiologist who, at the end of his career, accepts to come back to his home village to practice as a GP.